In Laos last week, I met several of the most inspiring and interesting travelers I’ve ever met, many of whom are eccentric in the most brilliant of ways. Most I met at hostels, but some I met randomly on group tours, sunsets, and more. It felt as if something about the “chill” and laid-back nature of the country unlocked a depth of conversation I am not used to having, across such a wide age and geographic range.

I wanted to focus on one topic we only really massaged around the edges instead of addressing head-on: tourism dependency. Tourism, either through its own execution or through incidental exposure to vulnerable communities, creates opportunities to “help” — to help those less fortunate, etc. So then what does it mean to help without disarming the recipient community of their agency?

I will start with an exceedingly innocuous example.

My last night in Luang Prabang, the former capital of Laos (beautiful, by the way), I spent at the main street night market with three wonderful friends from America, South Africa, and Spain. As we walked up to a food stall the young man exclaimed to us, “welcome! how are all of you doing?” We started a conversation, and two Chinese tourists walked by a minute or so later, to which he propositioned that they try the food out, this time in Chinese.

When I ordered I asked in English if he wouldn’t mind swapping out the white rice with brown rice, which he didn’t quite understand. So I asked him again, but in Chinese, to which he shook his hands and said he definitely wouldn’t be able to understand in Chinese.

To be clear, I don’t mind at all that I didn’t get to eat brown rice for dinner. The point is that the server (who was lovely) had shaped himself to speak only for basic tourist-food interactions (“how much?” “cash or card?” “one water, please”) because the rest was so esoteric.

Here’s a more troubling example:

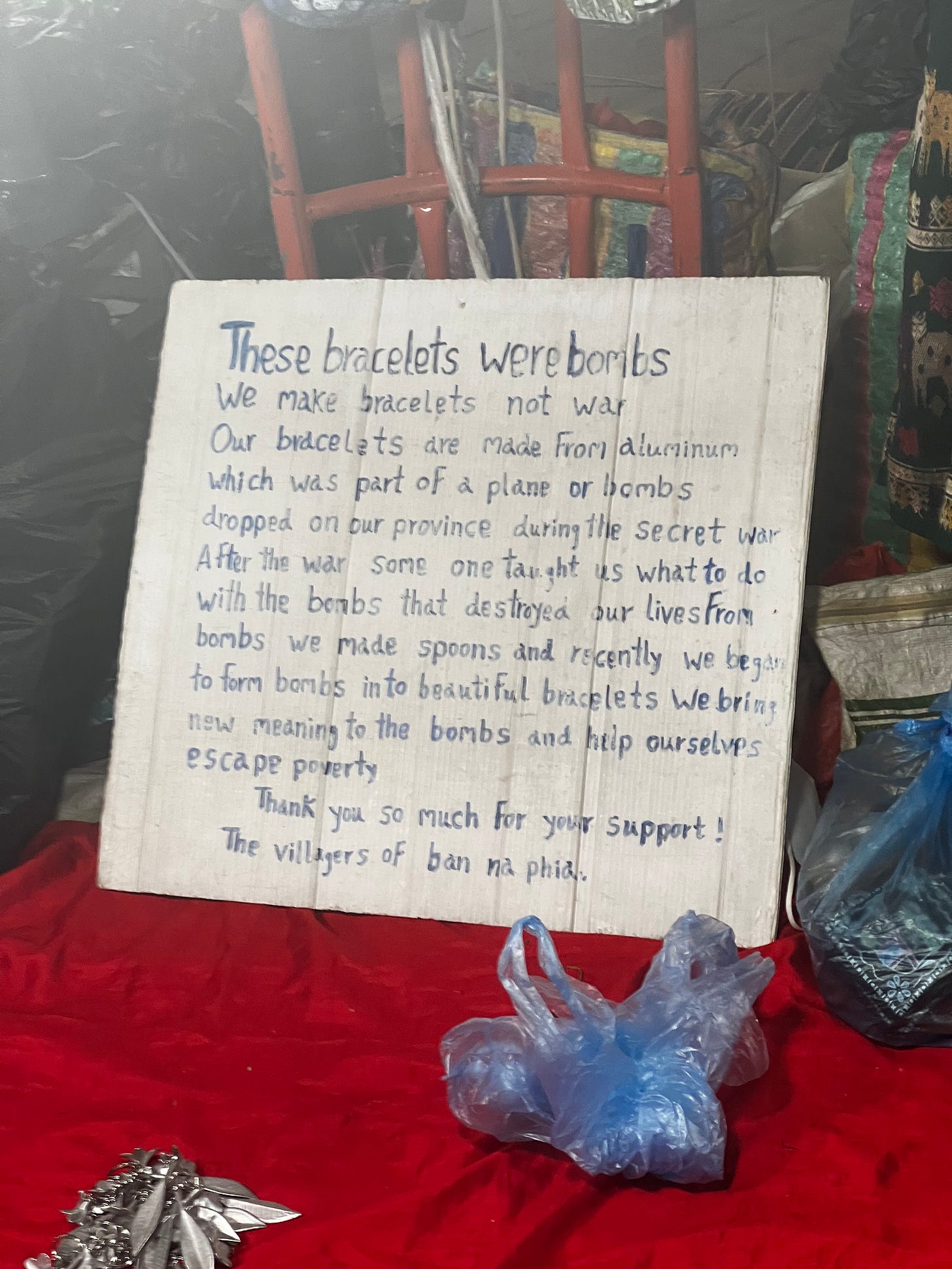

The previous day, at the same night market, I came across a vendor of repurposed bomb material, bombs from the horrible US-instigated secret war in Laos:

This signage was emotionally violent and persuasive. It would also appear rational to the sustainably-minded traveler, as the money goes directly to the village:

Although tourism can be a great form of wealth distribution, often as little as 5-10% of the money tourists spend remains in the destinations they visit. — World Economic Forum

Somehow the sign also confused me in a way that I couldn’t verbalize at the time. So I held my wallet and didn’t buy a bracelet, hoping to gain clarity soon.

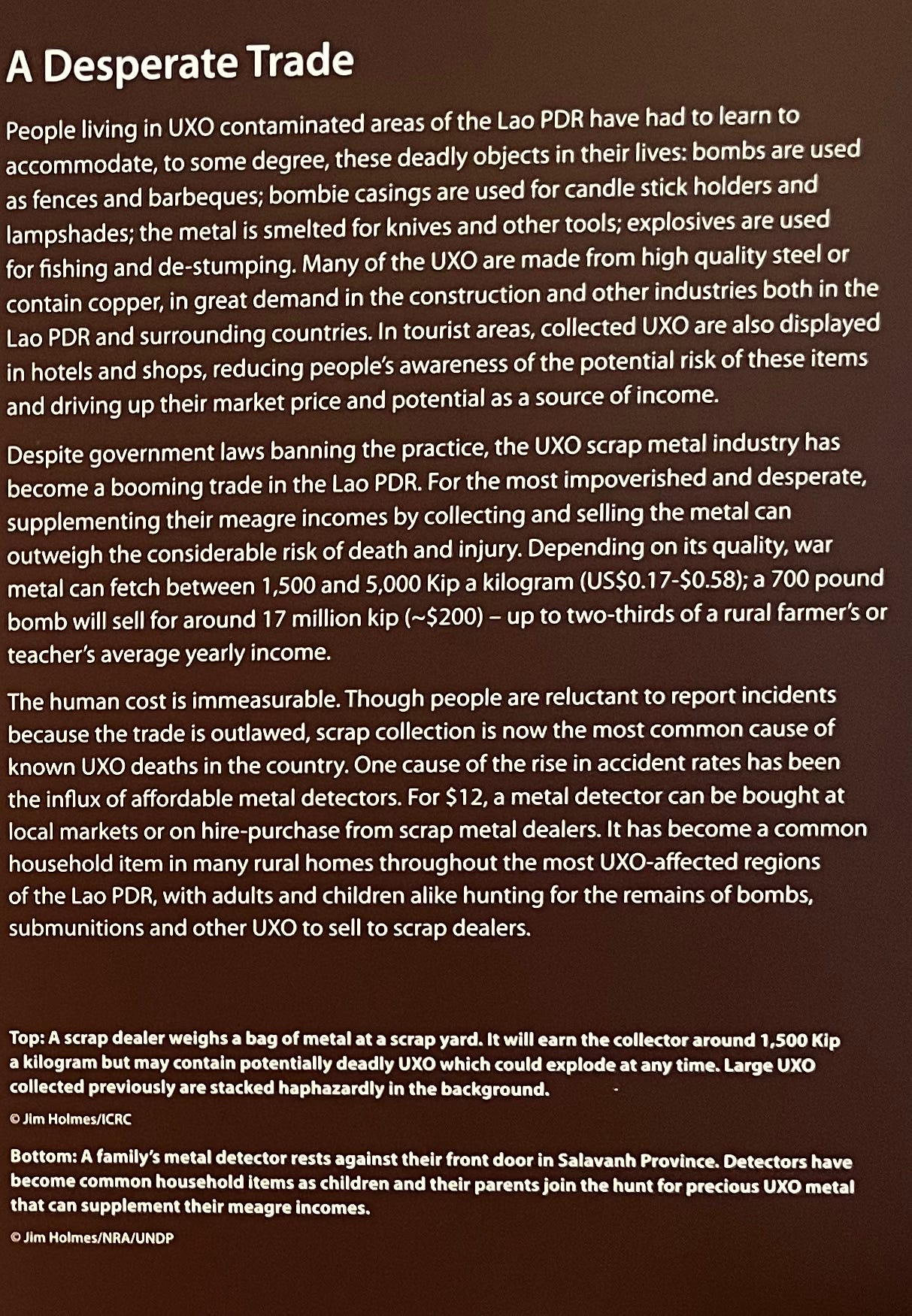

The next morning I took a trip to the UXO Lao Visitor Center, the organization responsible for much of the unexploded ordinance clearance in Laos as a result of US interventionism. Some harrowing information:

Laos was sucked into the Vietnam War as its own civil war became a proxy to the US fight against North Vietnam.

America dropped a quarter of a billion unexploded bombs (called bombies), and 80 million did not explode upon ground impact and so remain an ever-present threat to the Laotian people.

These unexploded bombs create ripple / chilling effects, analogous to a chilling effect to free speech but 1000x more violent (the analogy is my personal commentary, not the museum’s). It is dangerous to farm, to break ground, to create civilization, etc with the constant fear of a bomb that is not yet exploded. The threat is completely random and very difficult to prevent.

Here’s the clarity I gained, which is best explained by personifying the sign: the signage almost wants you, the tourist, to remain distanced enough from the historical/present context to forget that many of these bombs are still unexploded (an uninformed reader who just reads the sign would not realize at all that these bombs are still a threat to present life). That context becomes important because it suddenly paints the procurement process of these bracelets as much, much more dangerous. Often, it is children doing the work of finding these scraps.

The center talks more about the general scrap industry below, for those interested:

Obviously not suggesting any malicious intent here on behalf of the village, which has probably sold plenty of these bracelets to tourists. There is instead a clear question of whether it is a good idea to “help” an impoverished village by supporting an obstensibly dangerous practice, and whether it is at all possible to disentangle the two to empower the tourist to “help” in a way that isn’t just “feel-good” but that is actually sustainable.

To zoom out, the tourist’s mere existence in places like Luang Prabang deserves its own conversation, which I will entertain for a bit here.

Tourism dependency, whether it involves the politics of help or not, is unsustainable because tourism is unsustainable. It hurts the environment, leaves the local community dependent on seasonal travel (where seasons contract as our planet grows warmer), etc. Or, more simply — crowded touristy places aren’t so fun to anyone.

My first night in Luang Prabang, I visited Phousi Hill, a Buddhist temple with one of the most beautiful sunset viewpoints of the city. The view was pretty, the site crowded. The video below doesn’t do the viewpoint justice but you get a taste:

After a while staring into the sun, I struck up a conversation with the person next to me about the crowds. They reminisced that their last visit to Laos, several years ago, there was barely 10 people around them watching the sunset.

Later on, as we talked about our backgrounds, they mentioned briefly they had done travel livestreaming/vlogging work. I began to judge them for the ironic comedy of expressing frustration about a problem toward which they had somewhat contributed, before stopping myself to remind myself that simply by being here as a tourist I was also probably part of the problem.

Is there a red line? If not buying a bracelet made of bomb parts, why was it more acceptable for me to pay 30k kip to a temple and contribute to a process stripping the temple of its “holiness” as it is overrun everyday by tourists who clearly weren’t interested in its Buddhist features more than taking pretty sunset pictures. (I’m being cynical here for purpose of argument)

I was struggling to define my ethics, so I spent the rest of my time in Laos challenging myself to experiences that might help me answer my question.

(By the way, this is part of the unexpected reward of solo travel. Some of the things I did would be strange for a traditional 6-day trip to Laos, or just the fact that I could keep to my own thoughts about this topic for an hour on end if I wanted to).

As one example —

I spent a full workday during the middle of my trip volunteering at a primary school, Big Sister Mouse, to teach English. I am generally wary of international volunteer opportunities and often wonder whether they are more so opportunities for the tourist or the recipient, which happens to be relevant to the politics of help / sustainability of tourism which has been the (albeit messily assembled) general theme of this piece.

I was drawn to Big Brother / Sister Mouse for a few reasons:

The organization is quite clear on maintaining its agency. A few quotes:

“Helping at our Big Sister Mouse school, or at daily English practice, are the best way to make a difference when you're in Laos. We often hear from travelers who would like to volunteer in other ways. We appreciate the interest and support. But our language, culture, and ways of doing things are probably quite different from what you're used to. The suggestions above are the best ways to help.”

“If you expect to volunteer for a week or more, please let us know after your first day, so we can discuss with you if there are any special skills you have, that might be incorporated. For example, if you know traditional dances from your country, or can play guitar, or have art skills, and would like to teach those subjects, we'll be happy to see if we can arrange that. Please do not email us about volunteer opportunities, we cannot discuss them until after we've met you and you've seen what we do.” — I suspect this is as much about “we’ve seen what you do” as well.

Lots of voluntourism programs will ask you for hundreds/thousands and hide under the reality that much of that money is spent right back on you in the form of transportation, food, etc. Big Brother Mouse, as far as I can tell, doesn’t ship anyone from across the world into Laos to teach English. They instead just ask for a 10USD donation to already-present travelers, to cover the bus ride to the school, a home-made lunch, and the bus ride back. Extra money goes toward student excursions.

The article I cited above makes the claim that donating is more altruistically cost-effective than volunteering abroad.

Given I was already in Laos, however, this binary became slightly more complicated, not least because I now have an attached personal experience to that day. I have no idea how teachers match kids’ energy levels all day (I was exhausted after one hour). But I could tell we were giving the full-time teacher a much-needed break.

Let’s not imagine there aren’t any downstream consequences to something as innocuous as financial contribution.

At the macro level, the aid dependency debate (does foreign aid make recipient countries dependent on political will / contribution) is a staple of foreign policy. For those interested, here is a nice brief.

This isn’t to say that a random tourist giving a donation must necessarily become politicized. But if we’re being logically consistent, some of the same concerns remain, not least because volunteering is usually a strong persuasive component to donations. One question these organizations might be asking — how can we convince tourists to donate, without “wasting” too much of our money and resources on giving them a touristic experience?

One of those ways is reflected in the sign from above. An emotional heavyweight gut punch.

See how I’m going around in circles? A random traveler who spent a few days thinking about this in Laos isn’t actually supposed to have the answers to these questions — that much I acknowledge.

Maybe this honest recounting of my experience might spark a conversation or two down the line. If you’ve ever felt the urge to have/continue this conversation, I’m all ears.

I actually don’t know where this platform is going to end up, because I’m not expecting to be writing much here in the next few months. I’ll be away from the laptop most of May (cycling in Japan). Then I’ll be in DC this summer doing work. Maybe some posts but as of now I’m not going to make it an intentional part of my workflow like I did last summer. But stay around — plans always change, it seems.

Excited to talk more when things are less crazy! Especially about what different perceptions of voluntourist experiences, spots becoming overrun with visitors(your point about the temple becoming less holy was interesting), and subversion and agency in creating hypertourist/‘inauthentic’ experiences. Forgot to comment but also about your backpacking post. Have so much fun in japan🤩

After the last 10 weeks in Greece, I’ve been thinking about this for quite some time. Would love to share experiences once we’re back in the Bay!