students, have a sense of public responsibility. students have a sense of public responsibility

student power

Since the end of March I’ve written almost 80 pieces on this platform. Loosely motivated by a conviction to spread knowledge of political framing, I’ve fudged the line between journalist, commentator, educator, and activist (whatever that means). Now, I am not as arrogant as to claim all or any of these titles, but I will also admit that the lines between these professions were never very clear to me to begin with.

In a classic journalistic sense, I’ve platformed issues that didn’t affect my life, but that were life-and-death to many: the refugee crisis in Greece, Catalan independence, physician assisted suicide in Switzerland. Israel + Gaza.

But it’s not lost on me that my most read piece was personally motivated: a breakdown of affirmative action, written after the SCOTUS ruling in July.

I continued to write out of personal conviction this semester, swept away in lived experience amidst a politically turbulent Fall, and it is with this attitude toward writing front-on-mind that I reflect on the calendar year.

As I get ready to travel a whole lot more next calendar year (Iowa in Jan for the caucuses, then all over Asia for the Spring semester — tell me your recs!!) and re-engage my journalistic tendencies, I thought it would be fitting to end the year with a piece so personally motivated that it might as well have been extracted from my internal manifesto. And I’m inclined to think that bits and pieces of it are part of every student’s internal manifesto, which is why I’m sharing.

My freshman fall, I took an ethics seminar that one week asked the question, “What is the purpose of college for you?” Most people in the room, including myself, gave well-seasoned answers about learning, being inspired by our peers, and doing good in the world. Only one person answered with absolute confidence: “Money.” Her answer first landed bitter in my mouth, until I checked my privilege. Two years later, we’ve grown into good friends, and I see from her all the time a sense of public and civic responsibility, as well as a conviction to learn for its own sake, that I don’t see from many others.

What gives?

We were having two slightly different conversations. Most of us were providing musings on what we want college to mean to us while we’re at college, and she was answering what she wants college to mean to her after she’s done.

On college campuses, the doing-good-for-society discourse dominates, but much of the debate over the public/ethical responsibilities of elite college students projects into the future. The more “enlightened” of us all judge the people who “just” want to make money after college. We judge the McKinsey admits and the investment bankers and consultants until we remind ourselves that making money is how you survive in real America — and then it feels we’ve hit a dead end. Can’t blame ya for selling your soul!

This conversation is canon for anyone entering an elite university and it becomes stilted within a year or two. The reality is that many of the people who answered about learning or being inspired by peers or about doing good in the world will eventually take a job with salary as the primary consideration. In the same breath, many who have realized that money matters early on are then liberated to spend appropriate time in college on endeavors blissfully removed from moneymaking.

Those interested in imbuing college students with a sense of “bigger-than-thou” public responsibility therefore need to refocus on what goes on during college, where moneyed interest has a smaller chance of competing and where we can instead make use of the university money invested toward holistic residential life — to facilitate communities of empathy and advocacy, communities oriented toward public responsibility instead of private gain. I’m talking about students while they’re students, not students when they “grow up,” whatever that means.

Understanding student public responsibility in terms of the now rather than the future requires an awareness of the unique public perception of college students and the subsequent resistance to progressive student movements. Yes, I’m talking about public responsibility from the progressive lens only — it’s the vocabulary that I experience.

Students at elite universities are by and large the winners of the educational jackpot, which empowers us as the prospective winners of every future lottery to come our way. Students are powerful for that reason, and in the same breath, our caricatures are an obvious target practice for people who are trying to activate communities disaffected by the elite university system.

In many cases, this shapes up as a conservative critique of higher education. This critique labels elite universities (and their investments in students) as out of touch, a frame that sticks because elite universities are by and large out of reach — even elite public flagships:

An analysis of enrollment data at 18 elite public universities by The Hill found an average admission rate of 31 percent in 2022, down from 47 percent in 2012 and 52 percent in 2002.

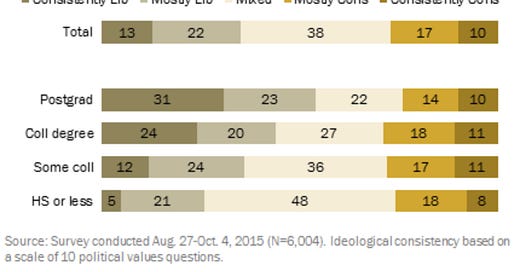

Elite universities are further characterized as havens for political progressivism, which then becomes inextricably associated with elitism.

These abstractions are not how many conservatives argue, however. Many frame their arguments, supercharged by implicit and explicit bias, by denigrating the downstream movements that progressive values inspire on campus (DEI, racial justice, gun violence, climate crisis). In many cases, these movements are seen as separate by the recipients of these attacks. But not by the perpetrators.

These criticisms then flood the news media. Take issues of race:

We tend to focus on the racism (as an example) embedded in these derivative initiatives, but we fail to engage the core antiderivative issue — elite students as “out of touch” with norms — at our peril.

Take gun violence. How did conservatives respond to an unprecedented series of protests against gun violence, after the Parkland shooting?

Harsanyi also wondered if "these kids understand that they attend schools that are safer than ever in a nation that has bequeathed them more freedom and wealth than any other group in the history of the world." — USA Today

Out of touch and privileged and unappreciative is what Harsanyi would say of these elite students.

To be clear, I’m not saying it’s inappropriate to attack racism and sexism and whatever-ism. But such a response is insufficient and plays off what conservatives know to be a progressive obsession with identity. The conservative attack on public responsibility is intersectional. All flanks of their turf war rely on the characterization of students as out of touch primarily, but also as elite and privileged, so the overall response must be equally intersectional and must return to the shared understanding of public responsibility as exactly the opposite of out of touch.

The least self-absorbed, the most compassionate commitment that a student could make is toward public responsibility, toward a larger-than-self movement. We cannot concede this frame because the alternative understanding is at best incomplete and at worst straight-up incorrect. I’ve listed out five musings on this topic below that might just empower any students who find themselves on the fence.

First - capitalizing on media attention

The conservative-waged culture war is one of many factors that brings a lot of media attention to students and schools.

Outside of conservative critique of higher education, media often takes the temperature of school campuses in gaging issues of significance and extrapolates the response to society at large. It’s very common to discuss gun violence in the context of school shootings, Israel-Gaza in the context of on-campus protests, and systemic racism in the context of DEI and critical race theory.

And in a media environment where a combined 72% of Americans receive regular news from Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, or Twitter, the generation most adept at social media has the power to pull the levers.

Happenings at school are a systematic proxy of society’s innermost turmoils. This is a power that every student can exercise while at school, a privilege that is invariably diminished as soon as they graduate and lose inside access to their school newspaper, networks of peers and professors, and more.

There is a strong case to be made, then, that public responsibility cannot wait for your college diploma. More and more students are answering the call.

When conservatives say that students are out of touch, they are hoping students don’t speak up in response because they are aware of the media attention they create. But what is considered “in with the times” and “out of touch” depends on the direction of the wind — when a loud audience of students are all saying the same thing like it’s obvious, the politicians are the group that starts to sound out of touch.

Second - reframing the purpose of higher education

While conservatives have been more than happy to frame students as out of touch, students are steadily realizing that such a frame is reductive to higher education, much less elite higher education.

School informs. At school, we learn how the powerful people of yesterday made mistakes that we cannot bear to repeat tomorrow. We learn how to conduct research, communicate our ideas, and engage people of different backgrounds.

The informed, yet out of touch student is a harder image to square than the ill-informed and out of touch student — admitting one characterization and leaving out the other reeks as misleading.

Take the same USA Today piece on gun violence protests:

Radio host Kevin McCullough said the march "was more irritating than anything else" and criticized the Parkland students who helped organize the event as an "angry, opportunistic" band of belligerent "media hyped know-nothings" who "spout their misunderstood self-researched 'facts,' lead chants of 'enough is enough,' and then play the untouchables when someone calls them on their inaccuracies." — USA Today

Aggravators like McCullough realize that describing students as ill-informed strips us of the persuasive power of our positionality — as students who are hand-picked investments of elite, high-quality institutions of education.

Students who convey that they are uber-informed possess political power that is arguably stronger than graduates, through subversion. We become integral parts of the discussion over public responsibility, while in school, precisely because it is impressive to others that we do a public servant’s job despite having not yet graduated.

Our combination of youth and maturity gets us through the door and to the table. We are not innocent like children, and we can carry public responsibility with youthful idealism and a dogged “get-shit-done” energy. It’s inspiring, and it’s depressing that we have to do it. But I would argue better now than later.

Third - the reckoning of empathy

College is a coming of age. College is an opportunity to form friendship deeper than we have ever experienced before.

In college, we see people at their worst — completely wasted after a party, or crying over their 8am midterm at 3am — and we love them anyway. We choose to be friends regardless of the inconvenience. Friendship in college is difficult and painful sometimes, which is what makes it meaningful.

College is a unique time during which students learn how to be “in touch” with others, where we learn how to interpret others’ pain as our pain, and where we allow our pain to be interpreted as others’ pain. This is fundamental to any sense of public responsibility and the complete opposite of any conservative characterization of progressivism and its “eliteness.”

I’ve written a lot on empathy so won’t talk about it more — but if you’re curious, here’s a discussion written around journalism.

Fourth - being confidently right is not enough

My only distinctive, substantive complaint about the student identity is that it seems too often we are satisfied being right. It’s not enough to be right; we must collectively act on the righteousness borne out by discussion and lived experience alike.

There are plenty of interpretations of the purpose of liberal arts education. Here’s my take: an incredible liberal arts education leaves students with the confidence to embrace just how little they know about the world around them. It encourages them to peel back the layers of meaning to be found in this world instead of remaining satisfied with the facts and figures they learned in the classroom.

Do not misinterpret the liberal arts mandate as a prescription that being right by itself cures a single soul in the world. That would be, in my humble estimation, the most accurate conservative attack on the liberal arts — basking in righteousness is akin to medical malpractice.

You might be willing to discuss gun violence in a seminar, but are you willing to discuss it with a survivor? With a gun owner from rural midwestern America?

You might be willing to debate Israel + Gaza with your journalism class, but are you willing to engage with someone living in Gaza?

Your recoil from this prospect is the gift-wrapped-and-delivered epiphany that righteousness itself is a delusional measure of any ability to advocate. It is at first contact with a personally affected party that you realize that your dispassionate intellectual interest should either become rapidly more empathetic or otherwise become subservient to their lived experience. In casual talk, you humble yourself.

The beauty of becoming involved in publicly responsible work while in college is that the exact combination of the two forums doesn’t just prepare you to deliver your beliefs more confidently; it ultimately teaches you to measure out your confidence against empathy and humility.

Those who attack liberal arts are betting on those who are satisfied as the winner of classroom debate, and they’re betting against those who see matters not as left or right, nor right or wrong, but as life or death — for a community affected by more than the participation grade.

When we’re okay with being right, we paint ourselves as out of touch, whether it’s fair or not.

Fifth - out of touch, reframed

Sometimes “out of touch” means “go touch grass and get off campus every once in a while.” Fair enough, but lacks teeth.

Sometimes “out of touch” means “not with the norms.”

This second meaning (or maybe even something more extreme) is probably how every single person who made a positive difference in this world was probably once described.

We Americans today consider anyone against the women’s vote as completely out of touch. We would have been out of touch a century and a half ago.

Naivete over established norms is the greatest asset of this generation of students, as it was in every generation prior. It’s being reframed as our greatest liability by some of the public servants today who were the student leaders of yesterday, student leaders who defied norms to push our country forward. See the hypocrisy?

Even if you’re someone who just likes the idea of having power (it’s ok, you don’t have to admit it out loud), you have great reason to become publicly engaged while you are still a student.

Students are a great threat to the establishment order. We’re somehow out of touch and also mainstream, which is a potent combination. Our words are read out loud by the nation. Our protest is a huge nuisance, and sometimes it moves mountains.

When the fundamental criticism of choice is “out of touch,” our empathy is resistance. Downstream, our empathy resists racism and sexism and every-other-ism. The last thing that many of the conservative establishment elites of society want is for students at elite liberal institutions to show a capacity to care for something that’s not just ourselves.

Acting on our empathy, together. That’s organizing.